Engineering a Direct Replacement 3D Printhead

From CAD and prototyping to manufacturing and supporting a base of over 2,000 satisfied customers.

At the time, the Lulzbot TAZ series of 3D printers had become a workhorse in many industrial rapid prototyping environments. Its popularity was driven by a unique combination of features: it was one of the first widely available printers with a large build volume, it was proudly designed and built in the USA, and it embraced the open-source design philosophy. Despite its professional adoption, it had one significant limitation: it was designed exclusively for the older, less common 2.85mm filament. This stood in stark contrast to the growing ecosystem of smaller hobbyist printers that were quickly establishing the more versatile and widely available 1.75mm filament as the new industry standard. As someone who relied on this printer regularly as my primary rapid prototyping tool, I experienced firsthand the frustration of this limitation through restricted filament selection, inconsistent availability, and the higher cost of 2.85mm materials.

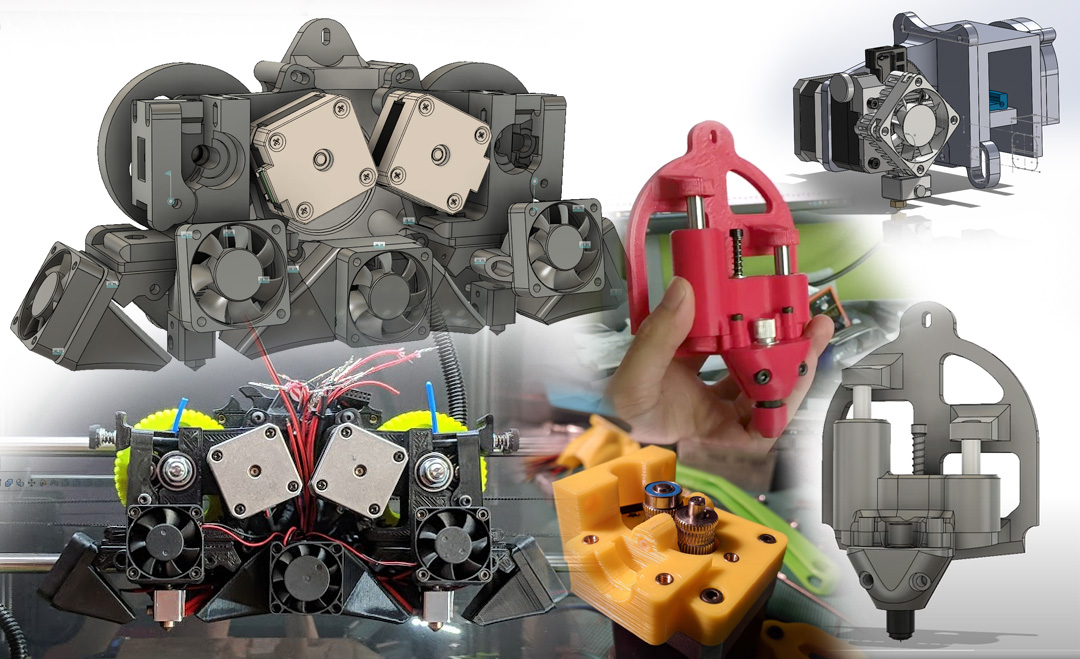

Capitalizing on the printer's open-source philosophy and its key feature of an interchangeable print head, my process began by reverse-engineering the stock unit to thoroughly understand how each component functioned and interconnected. This foundational analysis enabled me to incorporate my own user-experience-driven improvements into a completely new and enhanced version. The core design of this new print head was then progressively refined over many iterations to ensure both improved performance and seamless compatibility with the printer's existing hardware and standard slicer software profiles.

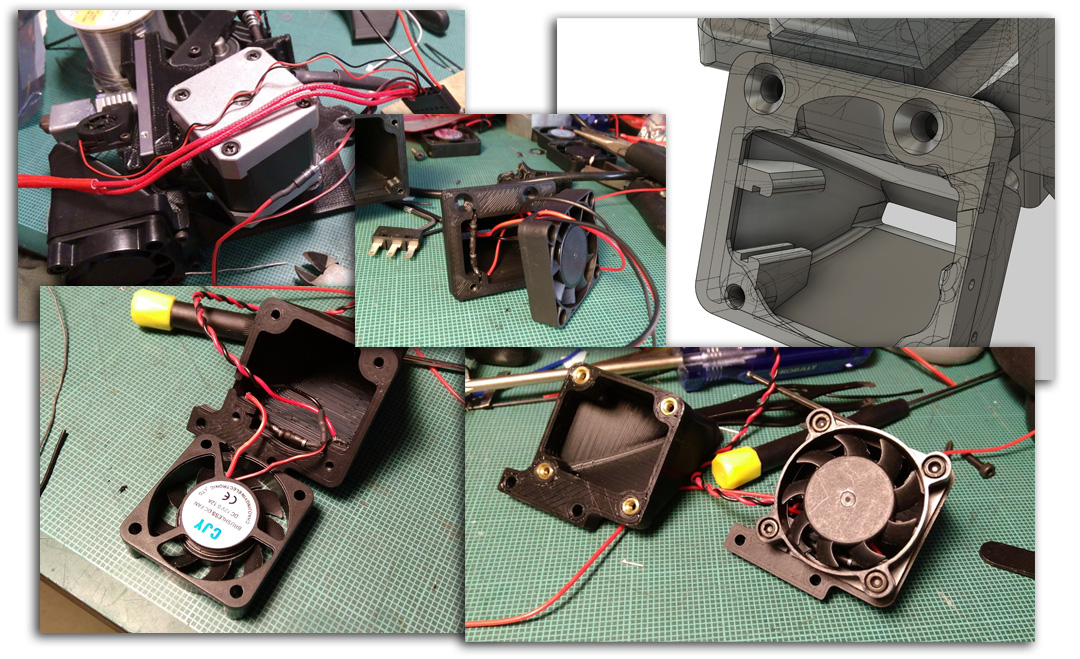

While replicating the improved mechanical design of the print head was straightforward, sourcing some of the original electronic components at an affordable cost proved to be a significant hurdle. The original 24V cooling fans, for example, were high-quality but prohibitively expensive, and lower-cost alternatives were incompatible with the printer's PWM fan speed controls, failing during the critical initial layers of a print. My solution was twofold: first, I devised an electronic workaround using a specific diode wired in series to enable the use of common, low-cost 12V fans. This generated considerable heat, which led to the second, more elegant innovation: I redesigned the fan duct housing to place the heat-generating diode directly in the path of the fan's own airflow, creating a clever, self-cooling thermal management system.

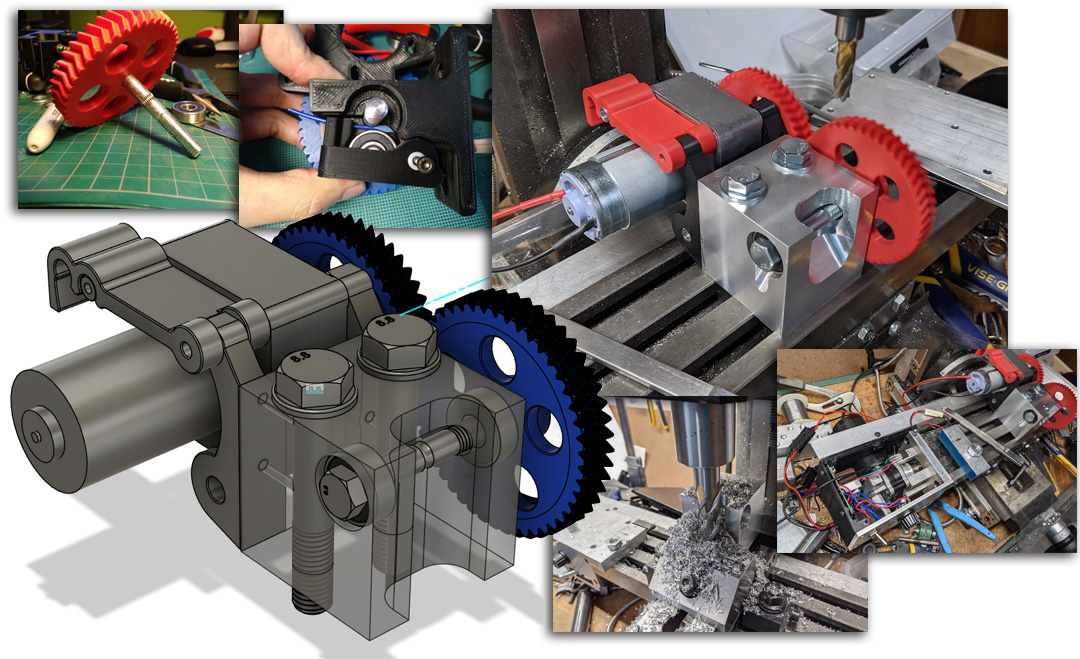

In addition to the 3D printed components, the shift to the 1.75mm filament standard required a complete re-engineering of the hobbed drive—the critical gear responsible for filament grip and extrusion. This was a complex mechanical challenge that went beyond simple CAD modeling. I experimented with numerous designs, testing various tooth shapes, counts, and depths to achieve optimal grip without grinding the filament. Each iterative prototype was manually machined on my vertical mill for precise testing. Finally, to ensure this perfected design could be manufactured with absolute consistency, I designed and milled a custom aluminum tooling fixture used exclusively for its production. This was just one of several key engineering hurdles that were overcome during this comprehensive redesign.

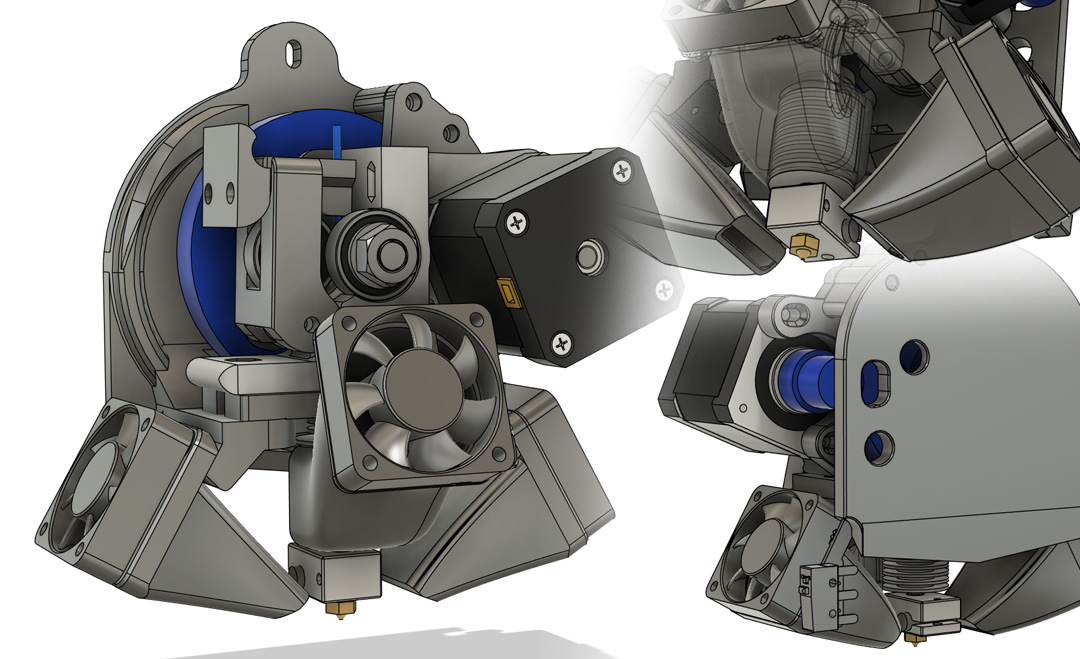

My initial success in building a lower-cost replica of the stock 2.85mm printhead led to a more ambitious challenge: creating a true 1.75mm version to unlock the printer's full potential via its interchangeable head system. Selecting the right 1.75mm hot end was the first step, and the high-performance model I ultimately chose was so dimensionally different from the original that it required a complete, from-scratch redesign of the entire printhead assembly. This presented a unique design challenge: I had to completely re-engineer the internal architecture while keeping the external appearance nearly identical to the original for the sake of customer familiarity. The main task in CAD was to skillfully conceal all the necessary internal geometric changes, while also integrating subtle visual cues to hint at the performance upgrades held within.

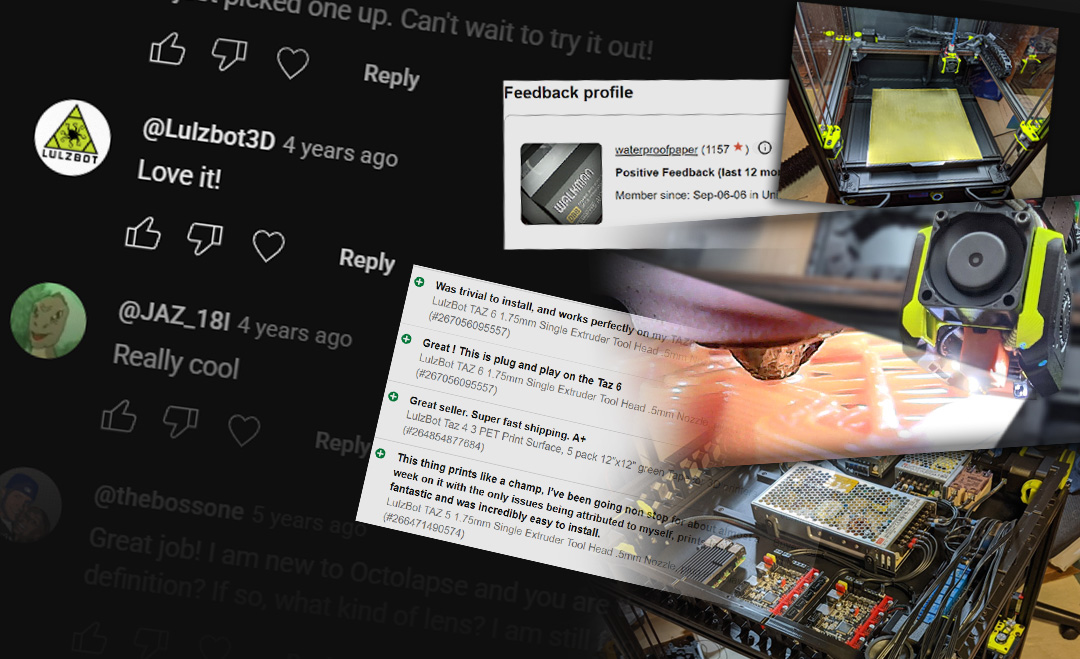

Ultimately, this venture successfully served over 2,000 customers, all of whom reported positive results and satisfaction with the printhead. This included many repeat customers who operate professional print farms, with whom I established long-term relationships by providing ongoing maintenance, support, and custom-order solutions. These custom projects ranged from building improved 2.85mm versions of the printhead to developing entirely new solutions like over-engineered dual printheads, vinyl cutting heads, and printheads adapted for different extruders or hot ends. In some cases, clients even entrusted me with their entire printers for comprehensive repair and customization.

The project's success and quality also garnered praise from the original manufacturer, Lulzbot, through both public comments and direct commendations from their internal team. Notably, when Lulzbot later released their own official 1.75mm printhead, many customers reported preferring and purchasing my version after trying the official one, citing my simpler, original-like design as more reliable, easier to unjam, and significantly easier to service.

Ultimately, the success of the replacement printhead venture both funded and inspired a deeper exploration into the entire 3D printing ecosystem. My focus expanded from pure hardware modification to also encompass printer controller software and innovative use-applications. This led to a variety of advanced projects, including a comprehensive design for a custom printer from the ground up, the construction of a highly customized Voron Printer, and the development of numerous problem-solving accessories. It was out of this period of focused innovation that my nozzle camera monitoring system was born, becoming one of my most impactful community projects.